Elizabeth Packard’s Terrifying Journey From Asylum Patient to Advocacy

How an angry husband institutionalized his wife and how she fought back to become an advocate for women’s rights and mental health rights.

exc-63ab4ce803ef120d57bb2720

Elizabeth Packard was a 19th-century who fought for women’s rights and mental health advocacy. She was born in a Calvinist household in 1816 in Ware, Massachusetts, and received a quality education from the Amherst Female Seminary.

Elizabeth Packard. Source: Womenshistory.org

Elizabeth’s husband

In 1839, at the urging of her parents, she married Calvinist minister, Theophilus Packard. He was 14 years her senior. In her book, “the Prisoner’s Hidden Life”, she mentions their first meeting. She was 10 years old, and she said she would have never considered a romantic relationship with him before the insistence of her parents.

In 1857, they moved to the village of Manteno, Illinois. By then they had six children and had lived in multiple states throughout the country.

Theophilus was known to be domineering. He resented a highly-educated Elizabeth questioning his beliefs. He was also pro-slavery and Elizabeth’s support for John Brown’s raid at Harper’s Ferry, Virginia embarrassed him.

Elizabeth goes public with her beliefs

In 1860, Elizabeth announced in the middle of church that she might join the Methodist Church because her beliefs aligned more with the Methodists. Reverend Theophilus Packard saw this as an act of defiance and openly questioned Elizabeth’s sanity.

After the event at the church, Theophilus arranged a covert operation. He recruited Dr. J.W. Brown to analyze her, while Brown pretended to be a sewing machine salesman. During their conversation, Elizabeth complained that her husband was domineering. She was also upset about him telling community members she was insane. Dr. Brown later testified that when the conversation switched to religion he “had not the slightest difficulty in concluding that she was hopelessly insane.”

Years later, Dr. Duncanson, a doctor and a theologian, testified for Packard’s sanity. He had spent hours talking with Packard and disagreed with Dr. Brown’s views on her religious statements. He stated that many of her ideas were similar to Swedenborgianism. Dr. Duncanson argued that many intellectuals and theologians in Europe favored New School ideas.

After talking with Dr. Brown, Theophilus decided to send Elizabeth to an insane asylum.

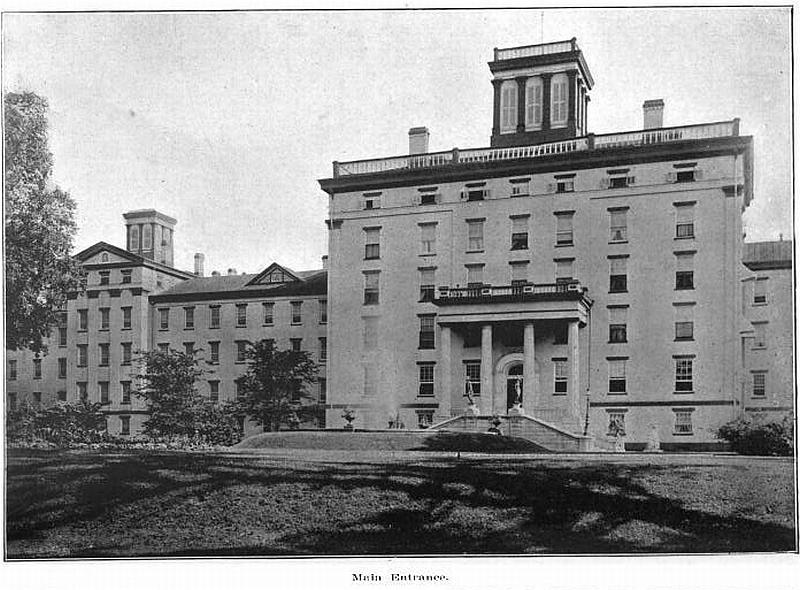

Illinois State Asylum where Elizabeth Packard was sent. Source: Asylumprojects.org

Elizabeth is sent to the Illinois State Asylum

On June 18, 1860, with crowds of people watching, the county sheriff removed her from her home. She begged him not to hurt her before he forcibly put her on a train to Jacksonville’s Illinois State Asylum.

According to Elizabeth, Theophilus became emotional in front of the asylum staff, openly weeping. But she knew it was a farce when she saw him leaving the facility with a wide grin on his face.

When Theophilus made a second visit, he asked if she rebuked her beliefs. She said no and he had her moved to a separate ward for the criminally violent. He left her with a trunk full of ragged clothes and rotten fruit.

Elizabeth was held in the asylum for three years without a trial or means of defending herself.

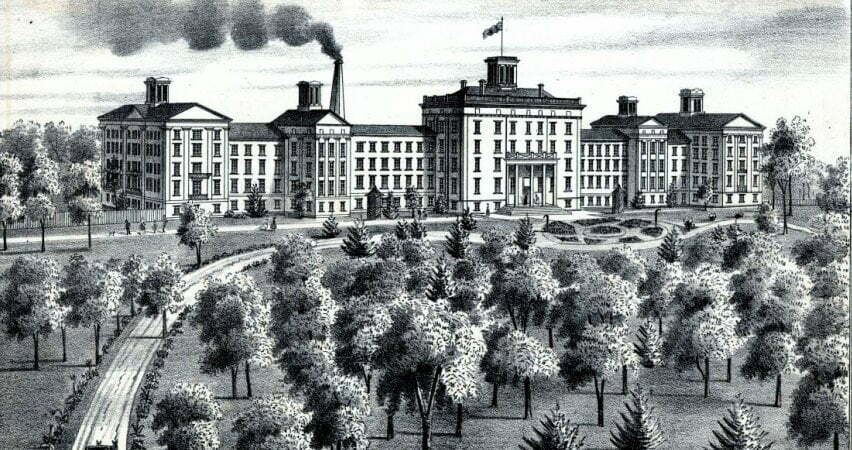

Elizabeth leaves the Illinois State Asylum

In 1863, one of Elizabeth’s sons turned 21 years old. He was able to legally petition for her release. Elizabeth resisted leaving because she was finishing a book about her experiences and lack of rights. She was also afraid her husband would lock her up somewhere else. Meanwhile, the Illinois State Asylum discharged her stating she was incurable.

Home imprisonment

When Elizabeth returned home, she was locked in a nursery for a month and a half. Theophilus nailed the doors shut. Even though it was winter, Theophilus refused to give her warm clothes. He forbid anyone from visiting her. She didn’t even have permission to ask for food or clean linen.

After throwing a letter out the window, describing her conditions and requesting help, a neighbor retrieved it. The neighbor was able to get a writ of habeas corpus issued on Elizabeth’s behalf.

The trial for Elizabeth’s freedom

Judge Charles Starr ordered that Theophilus Packard had to bring Elizabeth to his chambers in January 1864. Packard brought Elizabeth and the discharge statement from the asylum. The judge wasn’t convinced the statement justified Elizabeth being imprisoned in her own home. He scheduled a trial in nearby Kankakee, Illinois.

The trial officially named, Packard v. Packard, lasted five days.

Theophilus’s lawyers brought family members as witnesses that testified about Elizabeth. They stated Elizabeth disrespected her husband’s authority. She also threatened to leave his congregation, which they believe was proof Elizabeth was insane.

Elizabeth’s lawyers, Stephen Moore and John W. Orr, called witnesses that were not members of Theophilus’ church. These witnesses were familiar with the Packards. They testified that Elizabeth never showed any signs of insanity.

The final witness, Dr. Duncanson stated “I do not call people insane because they differ with me. I pronounce her a sane woman and wish we had a nation of such women.”

The jury deliberated for seven minutes. They ruled in Elizabeth’s favor.

An illustration of the Illinois State Asylum. Source: Asylumprojects.org

Elizabeth’s life after the trial

After the trial, Elizabeth returned to Manteno. She discovered Theophilus sold the house, her wardrobe, and all their furniture. He fled to Massachusetts with their children and all her money.

Elizabeth Packard devoted the rest of her life to social reform, using her experiences to draw attention to the poor state of mental health care. She spoke around the country, calling for legislative changes that gave mental patients more rights.

She supported herself by publishing books that supported the rights of married women and mental health patients. From her efforts and influence from her books, 34 bills were passed in multiple state legislatures, including a law passed by the Illinois legislature in 1869. The law required a jury trial before a person could be committed to an asylum.

She met First Lady Julia Grant and President Grant, and worked on a federal bill with lawyer Belva Lockwood, the first woman to argue before the Supreme Court. The bill was passed.

She also influenced the formation of The National Society for the Protection of the Insane and the Prevention of Insanity in 1880.

Packard died in Chicago in 1897. Her legacy lives on today as a pioneer in the fight for the rights of women, the mentally ill, and the protective rights of individuals from involuntary commitment.

Further Reading:

https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/elizabeth-packard

https://blog.library.in.gov/a-bill-drawn-by-a-woman-mrs-packard-and-rights-for-the-insane/

https://collections.nlm.nih.gov/catalog/nlm:nlmuid-2566020R-bk