The Italian Hall Disaster: a fateful Christmas Party

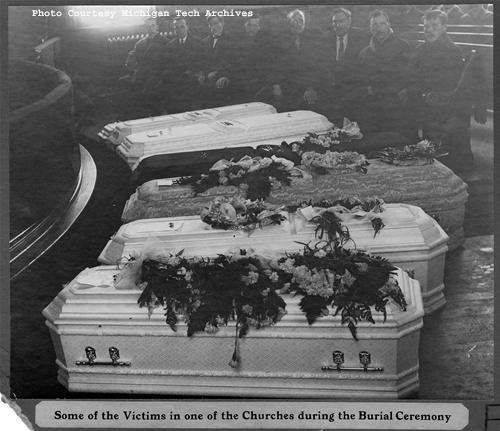

The coffins of Italian Hall Disaster victims. Photo courtesy of

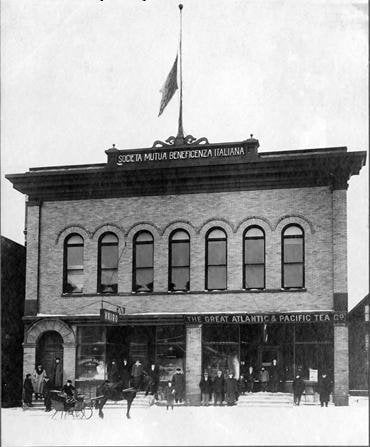

In Calumet, Michigan in the heart of the Upper Penisula’s Copper Country, on December 24, 1913, employees of a copper mining company and their families gathered for a festive Christmas celebration at the Italian Benevolent Society building. The party was sponsored by the Western Federation of Miners (WFM) union. But as the night unfolded, a single shout of “Fire!” would forever change the course of the town’s history.

Life in Copper Country

Copper was discovered on the Upper Michigan Peninsula in the 1840s. Mining companies popped up in the area and utilized a constant flow of immigrant workers. Calumet & Hecla (C&H) formed in 1865, was one of the largest mining companies. By 1907, it had over 21,000 employees.

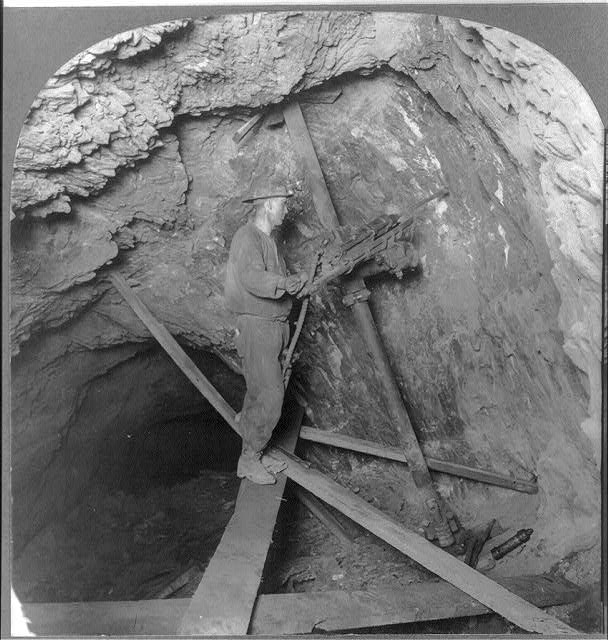

C&H like other mining companies, built towns for its workers. The company constructed libraries, schools, and other amenities for the workers and the workers’ families. However, these amenities hardly supplemented the low wages the workers received for performing some of the most dangerous jobs in the nation. The workers often worked 12-hour days, six days a week in the darkness of the mines. The company handed Eastern European, Italian and Finnish immigrants the most undesirable jobs. Despite the risks involved, medical expenses were not covered for these workers.

Meanwhile, the company controlled the workers’ lives. C&H, with a 15-day notice, could evict families from their homes. If a worker was fired they could evict the worker and his family at any time. They even evicted the widows and children of workers that died in the mines. Some children were orphaned.

The one-man drill

James MacNaughton was the general manager for C&H. He reportedly felt little sympathy for his employees. MacNaughton was solely focused on cutting costs and increasing production. With an interest in new technologies, he introduced the one-man drill invention into the mines.

Previously, the mining drills were operated by two men. The one-man drill slashed costs and doubled mining productivity. However, the drill would result in 50% of their jobs being cut. The workers also knew that the one-man drill was dangerous. They would no longer have a partner that could keep an eye on their partner’s safety. If something went seriously wrong, they would be alone in the darkness.

The 1913 strike

By mid-1913, discontent was brewing. The Western Federation of Miners called for a strike in July. Mining companies responded by calling in the sheriff, who deputized 200 Calumet & Hecla employees to help break the strike. However, per the Calumet & Hecla president, the deputies were not given guns. Strikers responded by throwing bottles, rocks, and steel projectiles at the Calumet & Hecla deputies. The National Guard intervened which allowed the mine to continue operations, but tensions remained. By November, the mining companies formed an anti-union group funded named the Citizen’s Alliance that denounced the WFM.

The Italian Hall Christmas party

By Christmas time area miners had been on strike for five months. To uplift the spirits of the striking workers, the women’s auxiliary of the Western Federation of Miners organized a Christmas party at the Italian Hall, a community center in Calumet. The hall, bustling with over 600 attendees, many of them children, was filled with joy and laughter. But the merriment was short-lived. An unexpected cry of “Fire!” sent attendees into a frenzy, rushing towards the only known exit—a narrow staircase leading to the street.

The tragedy

The panic was swift and deadly. The staircase became a death trap, with bodies piled upon one another. By the time the chaos subsided, 73 lives were lost, including 59 children. The tragedy was unparalleled, especially considering it occurred above ground, primarily affecting miners’ families.

“What happened is when people panicked, they tried to get out through the stairwell,” Jo Holt, a historian with the local Keweenaw National Historical Park said. “Someone tripped or people started to fall, and that’s what created the bottleneck. It was just people falling on top of each other.”

Al Harvey, a Calumet resident, was present the night of the Italian Hall Disaster. Harvey and the Chief of Police, Joe Caddell stayed to help dig party-goers out of the mess that had accumulated at the bottom of the stairs. In the Calumet News, Harvey recounted that “The hallway was jammed clean from the top to the bottom. There they were— jammed in there, one on top of the other. I have never seen anything like it.”

The aftermath

The aftermath was horrifying. As the dead were pulled from the pile in the stairwell, they were carried to the town hall, which turned into a makeshift morgue. Some families lost more than one child. Other children were orphaned when their parents died.

Coffins were express shipped to Calumet. The next few days saw a flurry of cooperation between funeral homes and churches as caskets were filled – small white ones with flowers atop for the children – and horse-drawn hearses were arranged.

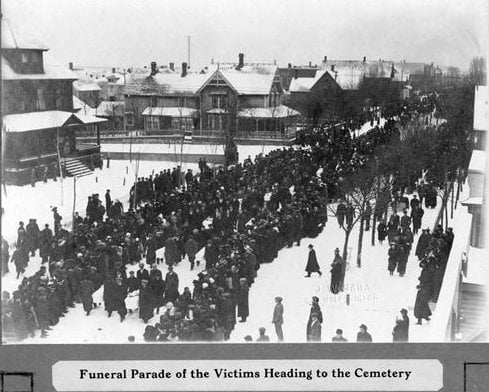

The funerals drew 20,000 spectators to Calumet, sometimes standing four-deep on the street as the procession passed them.

Eulogies were delivered in Croatian, Finnish and English. Huge crowds listened to the eulogies with some onlookers climbing trees for a better view.

The citizens of Calumet point fingers

In the wake of the disaster, rumors and accusations were rampant in the town. Some blamed a drunken patron from the saloon below. Others believed it was instigated by an anti-union representative who wanted to break up the striking workers’ party. Several witnesses in a federal inquest in 1914 testified that they saw a man yelling “Fire!” that had a Citizen’s Alliance button on his coat. Either way, many locals were angry at C&H and the Citizen’s Alliance.

Local newspapers published varying accounts and theories. Some papers mischaracterized details. Meanwhile, others made it difficult for family and friends to find their loved ones by misspelling names or printing names twice.

Rumors emerged later that the Italian Hall’s doors were designed to open inward, preventing the panicked crowd from pushing them outward to the street.

Other newspapers nationwide, especially in industrial cities like Detroit, New York, and Chicago, picked up on the Italian Hall story. They used it as an opportunity to highlight labor issues throughout the country.

Meanwhile, a relief committee made up of Alliance members collected $25,000 to aid the families of the victims of the Italian Hall disaster. The grieving families refused to accept the committee’s money, saying that the WFM had promised them aid. The committee members heard that Charles Moyer, WFM president persuaded the families not to accept the aid.

Enraged relief committee members visited Moyer at his hotel. They shot and kidnapped him. Then put the bleeding man on a train telling him never to come back to Michigan again. Moyer survived and held a press conference where he displayed his gunshot wound and promised to continue his WFM work in Michigan.

The legacy of the Italian Hall Disaster

The instigator of the “Fire!” shout remains a mystery. Whether it was a genuine mistake, a cruel joke, or a deliberate act from an anti-union figure, the motive is lost to history.

The strike eventually ended in April 1914, and workers returned to the mines. Deep divisions between Calumet’s strikers and company men lasted decades after the Italian Hall deaths. The events of what actually happened during the disaster are still hotly debated.

The “This Land is Your Land,” singer, Woody Guthrie brought the massacre renewed attention forty years later, writing “1913 Massacre.” A verse from the song reads “Take a trip with me in 1913, To Calumet, Michigan, in the copper country. I will take you to a place called Italian Hall, Where the miners are having their big Christmas ball.”

Following the 1913 Christmas Eve tragedy, the hall continued to be used for nearly five decades. In 1984, the Italian Hall was demolished. The two lots on both sides of the former building are owned by the National Park Service’s Keweenaw National Historical Park, which helps the village with maintenance and interpretive work.

The stone arch of Lake Superior sandstone that stood above the infamous stairway was preserved and is on the spot where the building stood.

Since 2000, on Christmas Eve, the Calumet-Laurium-Keweenaw Rotary Club places luminaries at the site of the former Italian Hall to honor those who tragically died on the property. The memories of the disaster still linger throughout Copper Country.

Sources:

https://www.mlive.com/news/2017/12/1913_italian_hall_disaster_was.html

https://commons.nmu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1028&context=upper_country

Other Michigan stories:

When Japanese bomb balloons landed in Michigan

Daily Life in Detroit in 1950 (footage)

The unforgettable horrors of the Bath School Massacre

1 thought on “The Italian Hall Disaster: a fateful Christmas Party”