Robert Owen’s innovative Indiana utopia

An idealized, 1838 engraving by F. Bate of London showing Robert Owen's unrealized vision for New Harmony, Indiana.

New Harmony is a historic small town in southern Indiana that was home to George Rapp’s Harmonist society and Robert Owen’s New Harmony utopia. Both societies were short-lived. But the New Harmony communities contributed to numerous social and scientific achievements in the early 19th century.

The first New Harmony utopia

The Harmonists were a German religious sect that separated from the Lutheran Church and immigrated to the United States. They believed in Christ’s imminent return and pacifism. They also practiced celibacy.

In 1804, the Harmonists built the town of Harmonie in Western Pennsylvania. However, they didn’t stay long. At Harmonie, they encountered an unsuitable climate and inhospitable neighbors.

In 1814, the Harmonists relocated to a new site along the lower Wabash River in Posey County, Ind. They called their new town New Harmony and enforced communal living with strict rules. They built homes for families and a Community House dormitory for young, single people.

By 1819, the residents had built 150 log homes, a church, stores, stables, and a tavern in the self-sufficient community. They cleared land for farming and produced well-known goods for places including New Orleans and Pittsburgh.

Robert Owen and the Industrial Revolution

Robert Owen was a successful industrialist and philanthropist from Wales. He owned cotton mills in New Lanark, Scotland, which he transformed into a model of humane management. At New Lanark, Owen improved the school system for school children. He also implemented life-long learning for adults.

Owen was an outspoken critic of the Industrial Revolution and its exploitation of workers. He proposed a social system based on communal property, equal rights for all, and universal education. He believed that human nature was shaped by circumstances around an individual instead of an individual’s greed and selfishness.

Growing weary of the negative influences from the growing Industrial Revolution, Owen saw the United States as a blank slate. He believed it would be a perfect setting for his utopian system.

Owen starts his New Harmony utopia

Owen journeyed to the United States in November of 1824. He met with prominent politicians in Washington and met with the Shakers. He journeyed to New Harmony to meet the Harmonists.

The Harmonists appeared well-clothed, well-housed, and well-fed to Owen. He also noticed they appeared unhappy. He believed their dissatisfaction stemmed from their religious fanaticism and lack of independence.

Owen seeing the town as a perfect spot for his experiments, purchased the town for $135,000 and invited people to apply for the available spaces.

Owen envisioned the community would serve as a model for “New Moral World” communities that would follow New Harmony. These communities would eventually transform world society. He believed it would all start in New Harmony where a community of 1,000 people would live in harmony and happiness, free from poverty, crime, foolishness, and superstition.

In January 1826, he brought his four sons and his wealthy business partner, William Maclure to Indiana. Maclure was a well-respected geologist. To jumpstart New Harmony’s intellectual heart, Maclure organized something called “The Boatload of Knowledge.” On a ship named the Philanthropist, a group of European and American geologists, entomologists, naturalists, zoologists, artists, and teachers took the month-long journey down the Ohio River from Pittsburgh to New Harmony.

Through William Maclure and Robert Owen’s posturing, New Harmony attracted men including Quaker Thomas Say, ‘the father of American zoölogy. Gerard Troost, a Dutch chemist and geologist, credited for being the father of American mineralogy, also joined. So did Charles Le Sueur, a French explorer, artist, and the first naturalist to classify fish species from the Great Lakes.

What was the town of New Harmony like?

New Harmony soon became famous as a center for innovations in education, and scientific research. A noticeable presence of curiosity, creativity, and tolerance emanated from New Harmony.

The residents established the first free library, a civic drama club, a museum, a newspaper, and a free, public school system open to men and women. The first headquarters of the United States Geological Survey was also located there.

The community implemented new forms of social organization, such as cooperative associations, labor exchanges, and women’s rights groups.

In the Nov. 1940 edition of the Atlantic, Katharine Dos Passos and Edith Shay described New Harmony as “Set down as if by magic in the fertile river valley of the Wabash was an Old World village of neat gardens, gabled roofs, avenues of black walnut trees. In this idyllic setting, nearly a thousand men and women of widely different backgrounds and nationalities were happily organizing balls, debates, concerts, theatricals, going on picnics, boating on the river, while engaged in the uplifting work of social revolution.”

Residents received credit at the town’s store in exchange for labor. Residents that didn’t work could purchase credit at the store with payments made in advance. In addition, Owen originally chose four committee members to govern the town, and the community selected three more members.

Children over two years old were taken from their parents and placed in common boarding schools. Residents trained the youth for a militia. However, they were taught that warfare was contrary to the beliefs of the New Harmony. Teenagers from the age of twelve to fifteen received technical training.

Adults from the ages of thirty to forty governed the homes. Meanwhile, residents aged forty to sixty assisted with the community’s external relations and some traveled abroad to bring recognition to the community.

The community urged all residents to meet often for discussion and debate.

Owen closed the distillery and banned liquor sales. However, visitors observed that the members, particularly the Irish, did a lot of bootlegging from the riverboats.

Numerous scientists and educators visited or moved to New Harmony after its founding including John James Audubon.

Sir Charles Lyell, an eminent Scottish geologist visited the community and noted “There is no church or place of public worship in New Harmony, a peculiarity which was never marked in any town of half the size in the course of our tour of the United States.”

Challenges

However, Owen soon realized that establishing his utopia was not as easy as he had imagined.

Owen faced many challenges in managing the diverse groups of settlers who came to New Harmony. Some were sincere believers in his system. However, some were also free-loaders, troublemakers, or simply curious. The town was also overcrowded and lacked housing.

Owen also dealt with external pressure from hostile neighbors, political opponents, and critics that were religious. Meanwhile, he failed to balance his own authority and vision with the personal aspirations and freedoms of New Harmony’s residents. He also struggled with receiving donations from wealthy patrons, whom he relied upon during his time in Britain.

Robert’s son William Owen, stayed in New Harmony while his father journeyed east for recruiting new residents. William had serious concerns regarding the feasibility of the New Harmony system.

William Owen wrote in March 1825, “I doubt whether those who have been comfortable and content in their old mode of life, will find an increase of enjoyment when they come here. How long it will require to accustom themselves to their new mode of living, I am unable to determine.”

When Robert Owen returned to New Harmony in April 1825, 800 residents now lived in the town which was more chaotic than when he left it.

New Harmony’s second utopia collapses

In 1827, the dissension intensified. The community was plagued by financial troubles, internal divisions, and residents abandoning the town.

By early spring, the members were leaving in great numbers. One day, eighty residents left. Signboards advertising property sales went up for properties designated for communal usage. Meanwhile, officials expelled a number of residents for not following the New Harmony codes.

Robert Owen quarreled with Maclure over money, and Maclure had Owen arrested. Afterward, Owen used $200,000 of his own funds to purchase the property and pay off the community’s debts. Owen left on June 1, 1827, just a little more than two years after the formation of his community.

In Owen’s farewell address, he told the residents they had a fine future ahead. He emphasized that New Harmony would rejoin “the ranks of the faithful.”

Owen’s New Harmony utopia was divided into smaller communities which led to further disputes. In 1829, New Harmony was dissolved. The land and properties were returned to private use.

Owen returned to Britain where he continued promoting his social reform ideas. He never gave up on his dream, but he realized that at New Harmony, he underestimated the complexity of his fellow human beings. Robert Owen died in 1858.

Owen wrote: “I was then ignorant of what everyone who attempts to govern men ought to know—that every person has within him a self-constituted judge…which will not be controlled by any laws or regulations that are not in accordance with it.”

Legacy

After Owen’s New Harmony utopia collapsed, the town continued being a beacon for academics and free thinkers.

Prince Maximilian Alexander Philipp of Wied visited in 1832. He spent time visiting the natural history museum, and collecting botanical specimens from the Indiana countryside.

Due to health issues, Maclure also departed Owen’s New Harmony utopia in 1827. Before his departure, Maclure created a trust that established the Working Men’s Institute. The institute which was the first free public library in Indiana, was both a public library and an education center. It was designed to assist laborers in learning about the sciences, nature, and history. Eventually, through Maclure’s benefactions, 140 libraries were inaugurated in Indiana.

Robert Owen’s sons

A few of Owen’s sons continued to have ties to New Harmony. David Dale Owen went on to become a noted geologist. David Owen’s museum and laboratory in New Harmony was known as the largest west of the Appalachians. At the time of Owen’s death in 1860, his museum stored around 85,000 items.

Headquartered at New Harmony, David Owen conducted the first official geological survey of Indiana (1837–39). Later, David became the first state geologist of Kentucky, Arkansas, and Indiana.

Robert Dale Owen, eldest son of Robert Owen Sr., was a renowned social reformer and intellectual. At New Harmony, he taught at the school and co-edited and published the New Harmony Gazette. Owen later moved to New York bringing the New Harmony Gazette with him. This paper, became the Free Enquirer, an important staple in the new workingmen’s movement.

In 1830, Robert published “Moral Philosophy,” the first treatise in the United States to support birth control. Robert was also an advocate for women’s rights and free public education. He opposed slavery.

He returned to New Harmony in 1834. As a member of the U. S. House of Representatives, Robert introduced a bill in 1846 that established the Smithsonian Institution.

Robert later served as chairman of the Smithsonian Building Committee. He had his brother David Dale Owen, choose the stone used to construct the Smithsonian Castle.

Robert also served as a delegate at Indiana’s constitutional convention in 1850.

Indiana University in Bloomington hired Richard Owen as a professor of natural sciences, where a building is named in his honor. In 1872, Richard became the first president of Purdue University.

The headquarters of the United States Geological Survey continued at New Harmony up to 1856. It moved to the newly built Smithsonian Institute, which Robert Owen’s sons helped establish.

The decline and rebirth of post-Owen New Harmony

New Harmony’s reputation for knowledge and free thinking continued into the 19th century until around the time of the Civil War. Afterward, the dwindling circle of people connected to the Owen family and New Harmony’s ideals kept the town going. New Harmony remained a small town. The population rose to 1,400 in the 1940s after oil was discovered nearby.

New Harmony today

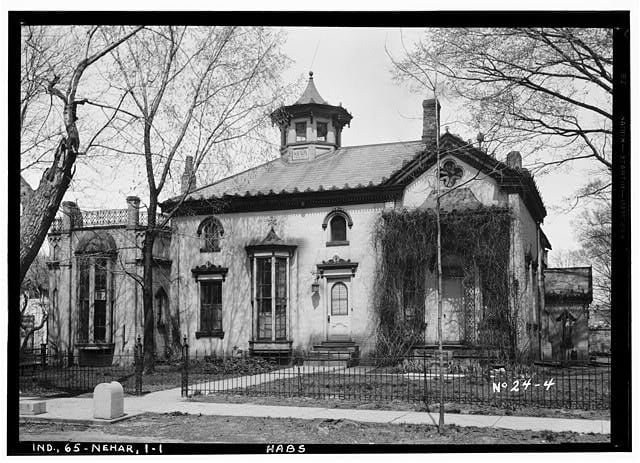

During the early 20th century, Mary Emily Fauntleroy, a descendant of the man who married a daughter of Robert Owen Sr., lead preservation efforts to save the historic buildings. Many of the Owen-era buildings are still standing in the New Harmony Historic District, which was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1966.

Today, New Harmony, Ind, is now a tourist town with artisan shops, antiques, and festivals. The New Harmony Historic District attracts visitors throughout the nation where they can learn how Owen’s New Harmony utopia led to changes in education, workers’ rights, women’s rights, and more in America.

Sources:

https://archive.curbed.com/2019/8/5/20748964/new-harmony-indiana-history-utopia

https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1940/11/new-harmony-indiana/654827/

http://plainshumanities.unl.edu/encyclopedia/doc/egp.ea.027

https://xroads.virginia.edu/~Hyper/HNS/Cities/newharmony.html