When earthquakes reversed the Mississippi River

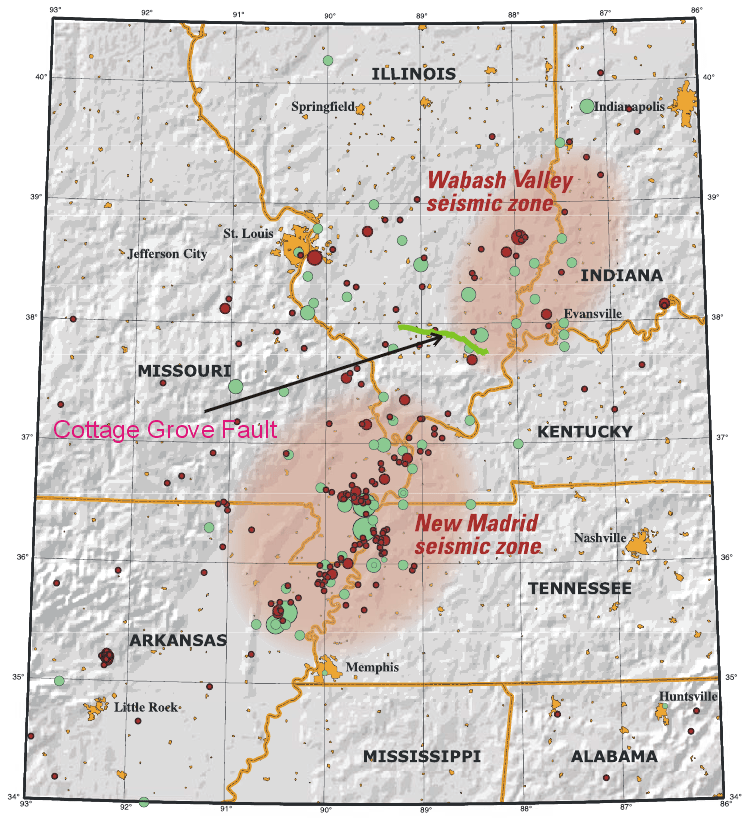

On December 16th, 1811 a catastrophic earthquake rattled the ground. This was the first of a series of catastrophic earthquakes in 1811 and 1812, centered in the Missouri Bootheel and Northern Arkansas regions. Estimates range from 7.4 to 8.0 magnitude during the December 16th, 1811 earthquakes.

In 1811, local residents near New Madrid, Missouri, began to notice a growing restlessness among their farm animals. Eyewitnesses reported seeing reptiles and other hibernating creatures, crawling out of their holes into the winter air, while local wildlife became tame.

On December 16th, 1811 a catastrophic earthquake rattled the ground. This was the first of a series of catastrophic earthquakes in 1811 and 1812, centered in the Missouri Bootheel and Northern Arkansas regions. Estimates range from 7.4 to 8.0 magnitude during the December 16th, 1811 earthquakes.

Stories say the 1811 earthquake toppled chimneys as far as Cincinnati and rang church bells hundreds of miles away in Charleston, South Carolina, and woke up the citizens of New York City. (Because of the older rock and colder ground, strong shaking was felt over an area 10 times the 1906 San Francisco earthquake’s coverage.)

“On the 16th of December, 1811, about two o’clock, a.m., we were visited by a violent shock of an earthquake, accompanied by a very awful noise resembling loud but distant thunder, but more hoarse and vibrating, which was followed in a few minutes by the complete saturation of the atmosphere, with sulphurious [sic] vapor, causing total darkness. The screams of the affrighted [sic] inhabitants running to and fro, not knowing where to go, or what to do—the cries of the fowls and beasts of every species—the cracking of trees falling, and the roaring of the Mississippi— the current of which was retrograde for a few minutes, owing as is supposed, to an irruption [sic] in its bed— formed a scene truly horrible.” – Eliza Bryan of New Madrid, Missouri, 1812.

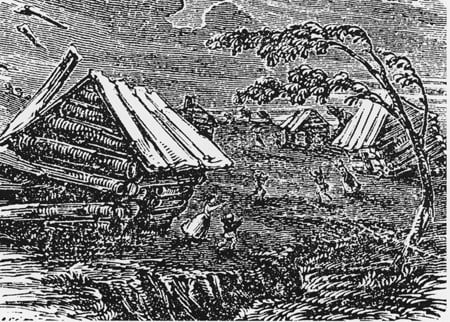

Devastation from the New Madrid Earthquakes

Sulfur seeped from the ground blanketing the skies. Boatmen reported the Mississippi River ran backward, while the land upheaval unleashed the river from its shackles, drowning multiple Native American villages. Loved ones vanished, likely falling into the black fissures spreading across the landscape. (Some fissures were over five miles long.) Ancient trees tumbled, barns were destroyed, and homesteads collapsed. Eyewitnesses reported the ground “rolling in waves,” while water and sand erupted from the ground.

Even an alarmed President James Madison wrote his friend and mentor, Thomas Jefferson, describing the shocks Madison felt in DC.

John Reynolds. the 4th Governor of Illinois described one of the 1811 earthquakes. “…Our family all were sleeping in a log cabin, and my father leaped out of bed crying aloud “the Indians are on the house” … We laughed at the mistake of my father, but soon found out it was worse than the Indians. Not one in the family knew at the time that it was an earthquake. The next morning another shock made us acquainted with it, so we decided it was an earthquake. The cattle came running home bellowing with fear…”

The local Native American tribes were convinced the quakes were a sign from the gods. Months before the earthquake a solar eclipse occurred. Local tribes interpreted as a sign of an upcoming war, and months later, a blazing comet appeared in the sky.

Shawnee leader Tecumseh, (whose name meant “Shooting Star” or “He who walks across the sky.” created a pan-Indian alliance. Months earlier, the U.S. military launched attacks on his tribes. Tecumseh after witnessing the first earthquake near Cape Girardeau, Missouri, rallied more warriors to join his alliance with Britain. The legends of the eclipse, comet and ultimately the earthquake, convinced many Native Americans to join Tecumseh’s forces.

The Earthquakes Will Happen Again

For decades, geologists believed the 1811-12 earthquakes were a one-time event. But archeological evidence suggests otherwise. “Sand blows” left over from previous earthquakes have been found buried under Native American pottery and spear points suggesting violent quakes occurred around 2350 B.C., 900 B.C., and 2350 B.C.

A 2009 study from the University of Illinois outlined the possible catastrophe. The lead author, Amr Elnashai, described the future earthquake in bleak terms. “All hell will break loose.” Elnashai said.

The report estimates a catastrophic earthquake could inflict $300 billion worth of damage in an eight-state area, including cities like Memphis, Nashville, and St. Louis. 7.2 million residents could be displaced.

Important bridges would be destroyed creating immense traffic delays. Hospitals would be damaged and cities with numerous brick buildings like Memphis would be devastated.

James Wilkinson, director of the Central U.S. Earthquake Consortium, is most worried about the earthquake’s impact on flooding. A potential earthquake would destroy the levees and locks that tame the river.

“The thing that, to me, makes the river scary is how much industry we have along it: there’s power plants, there’s chemical plants, there’s ports.” He says.

Today, the sleepy town of New Madrid, Missouri still rests on the infamous fault line giving the town the motto “It’s all our fault!” The displays at the New Madrid Historical Museum on Main Street are a reminder of the devastation caused by the New Madrid Earthquakes. Throughout the Midwest and parts of the South, there are still scars in the ground, cracks in buildings, and other remnants of the great quakes.

1 thought on “When earthquakes reversed the Mississippi River”