Crazy Horse’s death

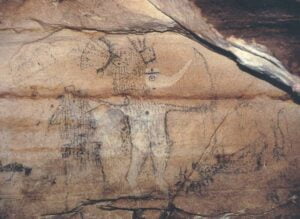

Illustration of Crazy Horse and his band of warriors on their way from Camp Sheridan to surrender to General Crook at Red Cloud Agency.

Crazy Horse’s battles against the United States government on Native American lands cemented his place in American history. The enigmatic figure’s achievements have inspired generations of Native Americans and resistance fighters.

Crazy Horse’s death on September 5, 1877, at Fort Robinson, Nebraska, marked the end of an era. The exact circumstances regarding how was killed are still debated.

Crazy Horse’s early life

Born around 1840 in present-day South Dakota, Crazy Horse, or Tȟašúŋke Witkó in Lakota, grew up during a chaotic period for the tribes on the Great Plains.

The United States’ expansion into the western states upended the lives of the Lakota and other tribes. Settlers threatened local game and skirmished with local tribes. Meanwhile, soldiers were sent in to protect the settlers.

Crazy Horse was living with his uncle Spotted Tail, and watched a group of soldiers attack Sioux leaders who were trying to mediate a dispute. Spotted Tail retaliated leading a group of warriors to attack the soldiers.

Crazy Horse returned from a bison hunt to discover the village was burned to the ground. Next to the burnt ruins were eighty-six people dead. He discovered a few survivors who informed him that the U.S. cavalry had decimated the village.

Crazy Horse and the Battle of Little Big Horn

Crazy Horse joined the resistance effort. His reputation as a warrior grew with the multiple battles he fought in. Crazy Horse’s ascendancy through the ranks culminated in his leadership during the Battle of the Little Bighorn in 1876.

The legendary battle, also known as Custer’s Last Stand, was fought between the allied warriors of the Lakota, Northern Cheyenne, and Arapaho tribes and the 7th Cavalry Regiment of the United States Army, which was led by General George Armstrong Custer.

Crazy Horse led around 1,000 warriors to flank Custer’s forces and seal the general’s infamous defeat and death.

This victory elevated Crazy Horse to folk hero status amongst the tribes. However, tales of his reputation spread to the U.S. Government who were both intimidated by him and eager to capture him.

Crazy Horse’s surrender

Following the Battle of the Little Bighorn, the United States government intensified efforts to put down the Plains Indians’ threat.

Crazy Horse’s Battle of Little Bighorn comrade, Sitting Bull went north to Canada. However, Crazy Horse and his warriors stayed to fight.

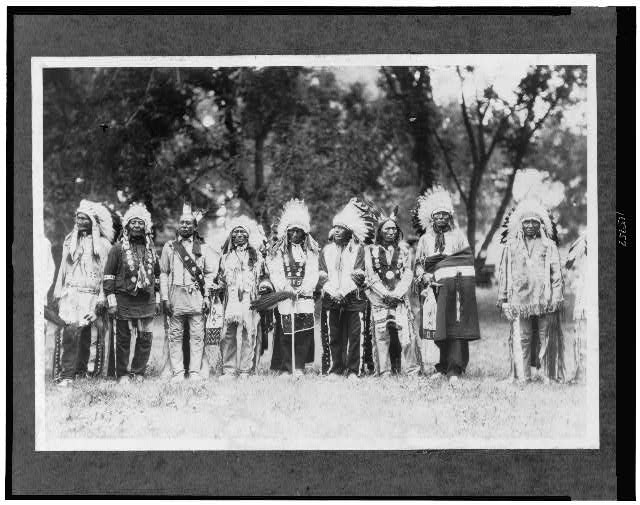

Eventually, with the harsh winter on the Great Plains and pressure from the U.S. Government, Crazy Horse negotiated with Lieutenant Philo Clark, who offered Crazy Horse and his starving men their own reservation for the warriors’ surrender.

In May 1877, Crazy Horse and his followers surrendered at Camp Robinson, Nebraska. They were promised amnesty and a reservation in the Powder River country, which is now located in northeastern Wyoming. However, the government refused to fulfill its promise.

Leaders grew jealous of Crazy Horse

Crazy Horse spent a few months in a village near the Red Cloud Agency, which was in the vicinity of Fort Robinson.

He hoped to live a quiet life on the reservation. However, despite his famous achievements and reverence from Plains tribes, he intimidated government officials and army officers in the area.

His fame also caused jealousy among other Oglala and Sicangu chiefs. The chieftains spread rumors that Crazy Horse planned to escape from the reservation.

In August 1877, a misunderstanding at a council meeting led to rumors that Crazy Horse intended to start an uprising leading to a new war. General George Crook was alarmed by the rumors and ordered the arrest of Crazy Horse. Historians surmise that chieftains also fed rumors to junior offices.

On September 4, 1877, Crazy Horse was taken into custody and brought to Fort Robinson, where he was to be imprisoned.

Eyewitness accounts of Crazy Horse’s death

The exact details surrounding Crazy Horse’s death are debated.

The most famous account, says that on September 5, 1877, Lieutenant Jesse M. Lee and several Native American scouts, including Little Big Man led Crazy Horse to the guardhouse. As they approached the guardhouse, Crazy Horse realized he was about to be imprisoned. Crazy Horse panicked, desperate to escape. Meanwhile, Little Big Man grabbed Crazy Horse’s arms, and a soldier named William Gentles fatally stabbed him with a bayonet.

Little Big Man’s eyewitness account

The Lakota scout refuted this account. At an 1881 Sun Dance, Little Big Man told Captain John Bourke that Crazy Horse had pulled a concealed knife. He told Bourke that he deflected Crazy Horse’s knife into the chief’s own side, fatally wounding him.

He said the guard’s bayonet missed Crazy Horse, leaving a visible gouge in the guardhouse door, which could still be seen in 1881.

Little Big Man’s account was convincing to Bourke. Before Sun Dances the Lakotas encounter a state of harmony where lying and baseless boasting are frowned upon. Bourke also believed Little Big Man wanted the American public to know that he (Little Big Man) was there during the death of the legendary warrior. He was part of history.

George Kills in Sight’s account

A relative of Crazy Horse, named George Kills in Sight gave an interview to Joseph Cash of the University of South Dakota in 1967. His grandmother was Crazy Horse’s cousin. He largely sided with the former account of Crazy Horse’s Death.

George Kills in Sight said “So there’s two guards on each side of the gate. And this Pine Ridge, members of the Pine Ridge, that escorted him, they told him that was a jail—in Indian. So he [Crazy Horse] turned around, and this guard—he was a white soldier—just run his bayonet through, through the guts. He didn’t shoot him or anything, just… Killed him there. They just let him lay there, and of course he was dead.”

Afterward, the U.S. Army handed his wounded body over to his grieving parents. Crazy Horse’s parents buried him in an unknown location, possibly near Wounded Knee Creek.

There are at least four possible burial locations listed on a state highway memorial sign near Wounded Knee, South Dakota.

The legacy of Crazy Horse

According to some tribal elders, the last words Crazy Horse said before he died were “Father, tell the People they can no longer depend on me.”

Crazy Horse’s legacy as a hero of Native American resistance and pride endures.

His name is a part of the American lexicon. His life has inspired countless books, films, and artworks.

Author Chris Hedges said, “there are few resistance figures in American history as noble as Crazy Horse…his ferocity of spirit remains a guiding light for all who seek lives of defiance.”

The Crazy Horse Memorial

The unfinished Crazy Horse Memorial, towers above a valley in the Black Hills of South Dakota. The colossal carving, visited by over 1 million tourists annually, depicts Crazy Horse atop a horse pointing towards tribal lands.

The finished sculpture will be the world’s second-tallest statue. Although it brings awareness to the legacy of Crazy Horse, it isn’t without controversy.

Crazy Horse Memorial controversies

Henry Standing Bear (“Mato Naji”), an Oglala Lakota chief recruited and commissioned Polish-American sculptor Korczak Ziolkowski to build the Crazy Horse Memorial.

Elaine Quiver, a descendant of one of Crazy Horse’s aunts, spoke out against the memorial. She stated that according to Lakota customs Henry Standing Bear needed permission from Crazy Horse’s family, but didn’t ask them.

“They don’t respect our culture because we didn’t give permission for someone to carve the sacred Black Hills where our burial grounds are. They were there for us to enjoy and they were there for us to pray. But it wasn’t meant to be carved into images, which is very wrong for all of us. The more I think about it, the more it’s a desecration of our Indian culture. Not just Crazy Horse, but all of us.”

The Ziolkowski family runs the non-profit memorial foundation that oversees the project. However, many critics have pointed out the family is making a sizeable income from Crazy Horse’s image using Korczak’s Heritage, Inc. The corporation runs the center’s gift shop, restaurant, and transportation to the site.