A Spanish Conquistador in Kansas

A trip into the interior of Kansas, searching for a city of gold, guided by a dishonest man.

exc-5fee3f0417af6f5d19fced5f

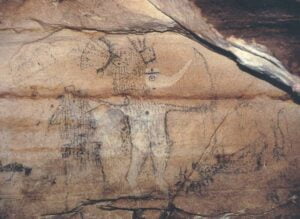

In 1881, a college professor near Lindsborg, Kansas, discovered a Spanish Coin. Later, pieces of chain mail, used for soldiers and horses, were found in six different sites in Kansas. What were they doing in the middle of nowhere, Kansas?

Some historians and archeologists believe they are of the remains of Spanish Conquistador, Francisco Vazquez de Coronado’s failed expedition to the city of Quivira.

Led by a Native American nicknamed “El Turco,” Coronado set off on a seventy-plus day journey across the Great Plains. After looking for the “Cities of Gold” in the Southwest, Coronado’s expedition discovered the cities were mostly pueblos. They weren’t flowing with gold like previous stories said they were.

El Turco persuaded Coronado there was one city left that had gold. El Turco guided the expedition across the plains to Quivira in modern-day central Kansas. This final expedition was Coronado’s last chance at acquiring riches and glory.

Who was Coronado?

Coronado was born into a royal family in Salamanca, Spain in 1510. By 1535, he moved to New Spain, present-day Mexico. Coronado married twelve-year-old Beatriz de Estrada from a wealthy family. He acquired a large estate and became governor of New Galacia in Northwest Mexico by the age of 28.

In 1539, Friar Marcos de Niza, a survivor of an expedition north to New Mexico, told stories about a golden city called Cibola. Niza didn’t visit the city, however, he was told the city was as large and wealthy as Mexico City.

Decades earlier, Cortes conquered the Aztecs and Cortes’s distant cousin Pizzaro, conquered the Incas. These two conquered civilizations brought enormous wealth and pride to the Spanish Empire. Viceroy of New Spain, Antonio de Mendoza, a personal friend of Coronado’s, was keen on replicating their success. Mendoza, like Coronado, took great interest in the tales of “cities of Gold.” He put Coronado in charge of an expedition headed north to find the cities.

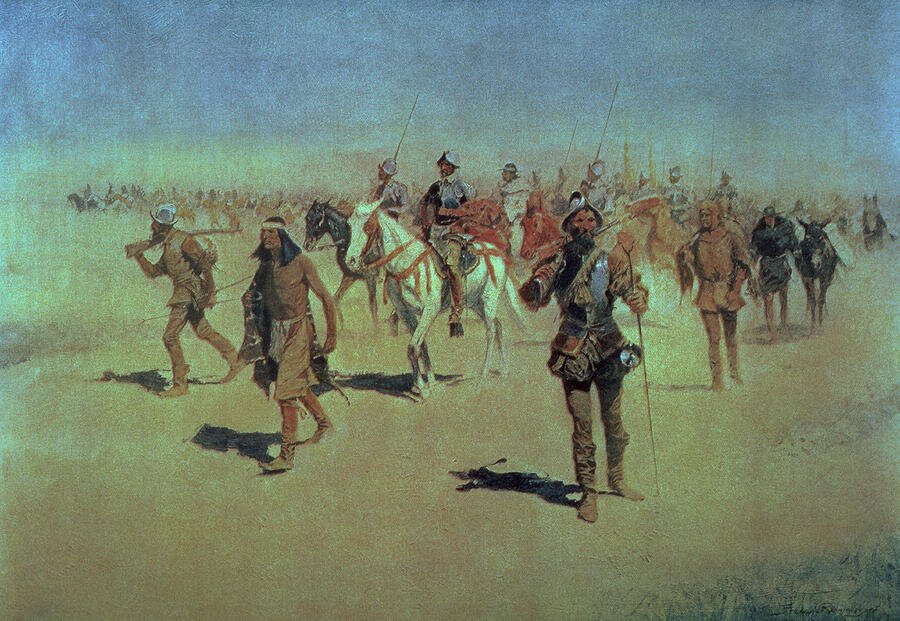

The expedition included 300 armed horsemen and foot soldiers, 1000 Indians and servants, and 1200 horses and pack mules. The Spaniards also brought light cannons, cattle, goats, sheep, and swine. A naval squadron was assembled to bring supplies up the Colorado River to resupply Coronado’s men.

Officially, it was cast as a missionary expedition. But unofficially, it was an expedition to find wealth and bring fame.

The expedition left in February of 1540. Exploring the present-day American Southwest, they failed to discover the cities of gold. (But they did discover the Grand Canyon). Instead, they discovered pueblos and small villages. None of them had stores of gold or citizens drinking from gold chalices.

Along the way, they met with tribes including the Zuni, Hopi, Tiguex, and more. The Spaniards wanted to “befriend” the Native Americans. The Spaniards, using their missionaries, asked them to repent of their sins and find God, otherwise they “could” be killed or their women and children sold into slavery.

The Native tribes didn’t take kindly to this. The “sins” the Spanish referred to, were the culture and customs passed down to their tribes by ancestors. The Spanish viewed these traditions as blasphemy.

There were also cases of Spaniards raping local women, while the Spaniards were guests in local Indian villages. Multiple skirmishes took place throughout the expedition including the conquering of Cíbola and the Tiguex War.

The Tiguex gave the expedition shelter until the Spaniards were chased out of town after a woman was raped. The Spaniards came back and slaughtered members of the tribe.

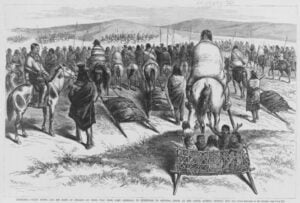

The Spaniards kept their promise. Hundreds of Native Americans were killed throughout the expedition. Women and children were hauled off as slaves.

Expedition to Kansas

In Coronado’s winter camp near the Rio Grande River, he met a Great Plains Indian nicknamed “El Turco” (the Turk). El Turco told the Spaniards stories of a city dripping with gold. He told them “There was a mighty river two leagues (nearly five miles) in width in which fish larger than a horse lived. It was a land where all inhabitants drank from jugs made of gold.” The city was called Quivira.

After coming up short in finding gold, Coronado knew this was his last chance of finding gold. Coronado left in the summer of 1541, with a much smaller expedition party. There were 30 mounted men and six foot soldiers. He also brought a friar named Juan de Padilla. El Turco told the Spaniards not to pack too many supplies. They would need space for all the gold they would be carrying back.

Guided by El Turco, they followed the paths that Indians and buffalo had carved out for centuries. However, the Spaniards started to suspect El Turco didn’t know how to reach the city. When they met up with another tribe, somewhere in Texas or Oklahoma, the tribe told the expedition they were headed in the wrong direction. The expedition was traveling in circles. The tribe told them to head northeast.

Along the way, the Spaniards saw a foreign landscape. The grasses moved like waves in the wind. They presumably heard the roar of thousands of buffalo stampeding across the endless plains. The thunderstorms were unlike anything they ever saw. Without trees to take shelter under, the sun must’ve beat down on them mercilessly.

On that alien soil, the plains Indians first glimpsed a strange, new animal. It was a horse. The same creature that would later transform them into horsemen warriors. Eventually, they crossed what is now known as the Arkansas River into Kansas.

After weeks of traveling, they reached Quivira and its Wichita Indian inhabitants. There was no gold.

Coronado wrote to the King of Spain.

“The province of Quivira is 950 leagues from Mexico. Where I reached it is in the 40th degree. The country itself is the best I have ever seen for producing all the products of Spain, for besides the land itself being very fat and black and being well watered by the rivulets and springs and rivers, I found prunes like those of Spain, and nuts, and very good sweet grapes and mulberries. I had been told that the houses were made of stone and were several storied; they are only of straw, and the inhabitants are as savage as any that I have seen.

They have no clothes, nor cotton to make them of, they simply tan the hides of the cows which they hunt, and which pasture around their village and in the neighborhood of a large river. They eat their meat raw like the Querechos and Tejas and are enemies to one another and war among one another. All these men look alike. The inhabitants of Quivira are the best of hunters and they plant maize.”

The angry Spaniards confronted El Turco. He confessed that the Pueblo tribes were tired of the Spaniards taking advantage of their resources. El Turco was told by chieftains to fabricate a story about a city called Quivira, filled with gold and other riches to get the Spaniards to leave. The tribes hoped the Spaniards would wander the plains until they ran out of resources and starved.

After El Turco’s confession, the Spaniards strangled him to death.

For 25 days in the summer of 1541 Coronado remained among the grass-hut villages of the Quiviran Indians, then returned to New Mexico.

Friar Padilla returned to the village years later and was killed by the Witicha tribe. He became known as the first Christian Martyr in the present-day United States.

Aftermath

Coronado and his expedition left New Mexico and headed back to Mexico City. Unlike the conquests of the Aztecs or Incas, the expedition failed to bring back extravagant treasures. The expedition was ridiculed. Viceroy Mendoza, who helped fund the expedition, called it a failure.

Coronado was broke after pawning his estates to fund the expedition. He also faced criminal charges. All of the charges against the expedition were cleared except for charges of cruelty against the natives. Coronado’s governorship was revoked.

Eventually, he gained a seat on the Mexico City council. Viceroy Medoza later forgave him and gave him a piece of land. But Coronado died at 46 in relative obscurity.

His expedition led to further ones, which set up settlements throughout the Southwest. The failed expedition didn’t dissuade future explorers to risk it all by traveling across the North American continent ie. expeditions to California, Oregon, Washington, and Canada’s British Columbia.

The Spaniards’ expeditions strongly contributed to the widespread demise of Native Americans. By the spread of disease, genocide, stolen lands, broken treaties, and forced assimilation, the continent was never the same.

Sources:

https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry.php?entry=CO062

https://www.legendsofamerica.com/kingdom-of-quivira-kansas/

https://www.pbs.org/weta/thewest/people/a_c/coronado.htm

https://www.nps.gov/coro/learn/historyculture/stories.htm

https://www.kshs.org/kansapedia/francisco-vasquez-de-coronado/17160

https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Francisco_V%C3%A1squez_de_Coronado#The_search_for_Quivira

https://www.psi.edu/about/staff/hartmann/coronado/coronadosjourney2.html

https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1500&context=greatplainsquarterly

1990 Coronado, Quivira, and Kansas: An Archeologist’s View Waldo R. Weldel National Museum of Natural History

“Coronado sets out to the north”

“Coronado sets out to the north”