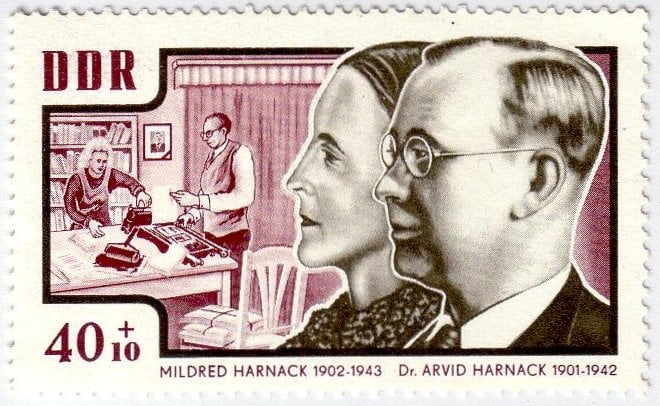

Defying the Third Reich: The legacy of Mildred Fish-Harnack

How an academic from Wisconsin gave her life defying the Nazis.

Mildred Fish-Harnack was an accomplished academic from Wisconsin. She resisted the horrors of Nazi Germany while disseminating intelligence to the U.S. and Soviet Union. Even though she gave her life resisting the Nazis, her story isn’t in American textbooks. How did she end up in the crosshairs of Hitler’s wrath? Why is her story not well known?

Early life

Born in 1902, Mildred Fish grew up poor on the west side of Milwaukee in a series of boardinghouses, the youngest daughter of an unstable father. She grew up close to “Sauerkraut Boulevard.” Although she wasn’t German, Mildred learned how to read, write, and speak the language.

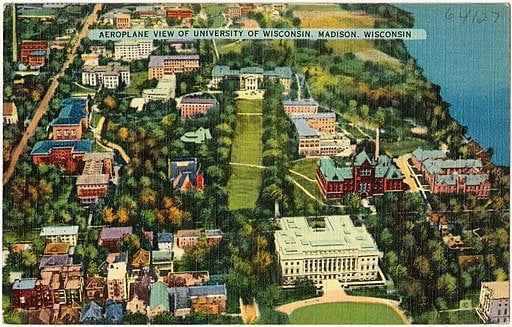

Mildred attended the University of Wisconsin in Madison, where she earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees, and taught English as a grad student.

At UW, Mildred joined a group of students led by a professor known for lectures on capitalist corruption. They met on Friday nights to talk politics. They were described as “a group of student revolutionaries.”

Arvid Harnack, a Rockefeller Scholar from Germany, came from a family of academics. He was on a fellowship while attending UW–Madison and was working on achieving his second doctorate. Arvid met Mildred when he went to the wrong building and ventured into her class.

According to a University of Wisconsin blog post, “He went up and introduced himself. He apologized for his faltering English, and she apologized that she didn’t speak German very well. And he proposed he study English with her and she study German with him. And that was the beginning of the romance.”

They married in 1926.

Moving to Germany

Mildred moved to Jena, Germany in 1929, where she started working on her doctorate in American literature at the University of Jena.

In 1930, she moved to Berlin to be closer to her husband. Months later, Mildred taught modern American literature at Berlin University (called Friedrich Wilhelm University at the time), She was one of the first Americans on a faculty that included Albert Einstein. According to a story in The New York Times, the position didn’t last. Fifteen months later, the university fired her for not being “Nazi enough.” Her time in Berlin reinforced her Marxist views.

Mildred also was a member of the American ex-pat community where she befriended Martha Dodd, daughter of William Dodd, Franklin Roosevelt’s ambassador to Germany. She and Martha were members of a salon that freely discussed current events and revolutionary ideas.

In 1933, she and her husband visited Moscow where they met a senior official of the NKVD. The senior official named Osip Piatnitsky, convinced Arvid to become a Soviet agent. While they were away, Hitler became Chancellor of Germany.

Living in Nazi Germany

To cover Arvid’s new role as a Soviet agent, Arvid joined the Nazi Party in 1937. He also accepted a job in the foreign currency department of the Reich Ministry of Economics.

Soon afterward, he joined the Herren Klub, an exclusive circle of prominent and influential Germans. The Herren Klub included manufacturers, aristocrats, bureaucrats and high-ranking officers from the Army, Navy, and Air Force. Arvid used many of these sources for valuable intelligence.

Arvid Harnack worked his way up to the rank of Oberregierungsrat (Senior Government Counsellor). This position gave him access to Nazi Germany’s foreign trade reports, which he forwarded to the NKVD.

In June 1938 the Soviets reported that Harnack had sent them “Valuable documentary materials on the German currency and economy, secret summary tables of all Germany’s investments abroad, the German foreign debt. He also sent “secret lists of goods liable to importation into Germany. Germany’s secret trade agreements with Poland, Baltic countries, Persia, and others. Valuable materials concerning the secret foreign service of the German Ministry of Propaganda.”

Meanwhile, in the mid-1930s, Mildred’s work began to be noticed and she became a published writer. She wrote essays on literary figures including William Faulkner. In 1936, she published an English translation of a biography of Vincent Van Gogh.

In support of the translated biography, she visited New York in 1937. Her friends and family noticed she was unusually coy and seemed frightened.

Later in 1938, Fish-Harnack worked on her doctoral dissertation, “The development of contemporary American literature in some of the main representatives of the novel and the short story”. She was awarded her doctorate at the University of Giessen in 1941.

In October 1939, she applied for the Guggenheim and Rockefeller fellowships in the hopes of fleeing Germany but was refused. In 1941, with the war going on, English language lecture positions vanished. She worked as an English-language tutor at the Foreign Studies Department of the Friedrich Wilhelm University.

The Red Orchestra

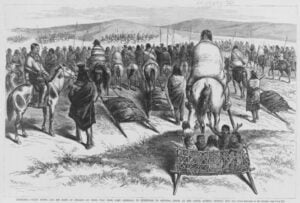

Meanwhile, sometime in 1938, Arvid and Mildred became active within a group the Abwehr nicknamed “the Red Orchestra.” The Red Orchestra published underground newsletters and sent economic intelligence to the U.S. and Soviet embassies in Berlin. At the same time, they helped Jews escape.

After Germany invaded Russia, the group transmitted military intelligence to Moscow via radio “concerts.”

Mildred translated Franklin Roosevelt’s speeches and American news reports into German. Then the translations were published in leaflets and quietly distributed to Germans that were flooded with Nazi propaganda.

Arrest and execution

In 1942, after German counterintelligence deciphered a Red Orchestra transmission, they started arresting members of the network. Mildred and Arvid fled to Lithuania. They planned to escape to Sweden, but the Gestapo captured them. Failures in basic espionage protocol led to their capture, including using real names in transmissions.

The Gestapo viciously tortured Mildred and Arvid for information.

Afterward, a kangaroo court sentenced Arvid Harnack to death on 19 December after a four-day trial. He was executed three days later at Plötzensee Prison in Berlin. He was hung using a foot-long rope, which prolonged his suffering.

Mildred was sentenced to six years of hard labor for the crimes of treason and espionage. When Herman Goring heard about the verdict, he reportedly was furious. Hitler decided not to endorse the verdict and had her retried and executed.

A prison chaplain saw her before she was guillotined in 1943. Her condition alarmed the chaplain. He noticed her hair thinned out significantly, her breathing was heavy, and her spine looked like a question mark. Mildred spent her last days translating a Goethe poem. She was 40 years old when she was executed. Mildred was also the only non-military, American citizen executed by Adolf Hitler on German soil.

Her last words were reportedly “And I have loved Germany so much.”

Her executioners handed her body off to a German anatomy professor who was studying the effects of imprisonment and execution on a female’s reproductive system. Afterward, he gave what was left to a friend of hers and he had the remains buried in Berlin’s Zehlendorf Cemetery. She is the only member of the Berlin-based anti-fascists with a marked burial site.

The legacy of Mildred Fish-Harnack

It’s unknown how much of Mildred and Arvid’s efforts hurt Nazi Germany.

Stalin ignored Arvid’s intelligence revealing Hitler’s plans to invade the Soviet Union. Nevertheless, who knows how many hands their leaflets and information reached in Nazi-occupied Europe?

With the Cold War raging after World War II, the U.S. ignored Mildred Fish-Harnack’s legacy. The CIA labeled her and Arvid as Communists. That eventually changed. In 1986, Mildred Fish-Harnack Day was created in Wisconsin.

A sculpture of Mildred now sits at Madison Wisconsin’s Marshall Park. Representatives from eight German universities attended the dedication service.

Sources/Further Reading

https://womeninwisconsin.org/profile/mildred-fish-harnack/

https://news.wisc.edu/mildred-fish-harnack-honored-as-hero-of-resistance-to-nazi-regime/